May 20, 2025

Why North America Needs Dual-Mode High Speed Trains

ABOVE: A Madrid - A Coruña high-speed service consisting of a RENFE class 730 (Talgo 250 Dual) operating under diesel power on the old line between Zamora and Ourense, before the new electrified high-speed line was completed. PHOTO CREDIT: David Gubler via Wikipedia

The Need for Dual-Mode High Speed Trains

California High Speed Rail (CaHSR) has a major problem, but a problem with a partial intern solution that on this side of the nation would benefit manufacturing— and perhaps even passenger rail service—in Upstate New York. And the partial solution is one many who ride Amtrak along the Empire Corridor are familiar with: dual-mode trains.

The CaHSR project was authorized by a 2008 statewide ballot with Phase 1—some 494 miles between San Francisco and Anaheim—with estimated cost of $45 billion with completion in 2020. Today the 171 mile “Initial Operating Segment (IOS)” in the Central Valley between Bakersfield, Fresno, and Merced is estimated to cost $30-33 billion with completion in 2031. Worse, the inspector general of the CaHSR authority has determined that the IOS is unlikely to be operational by 2033 and that there is an up to $7 billion budget gap to complete it.

The reasons for the failure of the CaHSR project to be competed anywhere near to on time and budget (while China has built the largest HSR system in the world) are several, but all seem to involve consultants and lawyers. The CaHSR authority lacked the institutional knowledge and organizational capacity to plan and build the system itself, instead outsourcing it to expensive private sector engineering consultants who seemingly also lacked the necessary knowledge—but where well paid anyways.

The regulatory environment led to never ending reviews and consultations, while private landowners waged a grinding legal battle against eminent domain land acquisition for the 220 MPH right-of-way through existing farms, businesses, and homes. All of this caused delays piled upon delays, cumulatively adding both billions of dollars and years to the completion of the already aggressively ambitious mega-project.

Under Gov. Galvin Newsom, project management has been reformed, with more expertise and staffing brought inhouse to the CaHSR authority. Still the problem of funding remains—where will the many tens of billions needed to connect the Central Valley IOS over the mountains to Los Angeles and the Bay Area come from? While the project has dedicated funding of about a billion annually from the state’s cap and trade program, this alone is insufficient.

Long derided on Fox News and elsewhere as “a train to nowhere” due to the struggle to build between Fresno and Bakersfield, the project today is under political attack at both the state and federal level, with critics decrying it as a massive boondoggle that should be terminated. And embarrassingly the privately led “Brightline West” high-speed rail project between Las Vegas and SoCal (Rancho Cucamonga) will likely have trains running years sooner than CaHSR, despite construction started this year (2025) with completion in late 2028.

Dual-Mode Trainsets

The sooner that CaHSR has trains running the better, getting the public something they can ride and benefit from should boost support for finishing the mega-project in some form to the Bay Area and SoCal. And the sooner the trains can run directly to Sacramento, Oakland, San Jose, and San Francisco—major population, economic, and cultural centers—the better as well, providing a one-seat ride from the midsize cities of Fresno and Bakersfield to the state capital and two global cities.

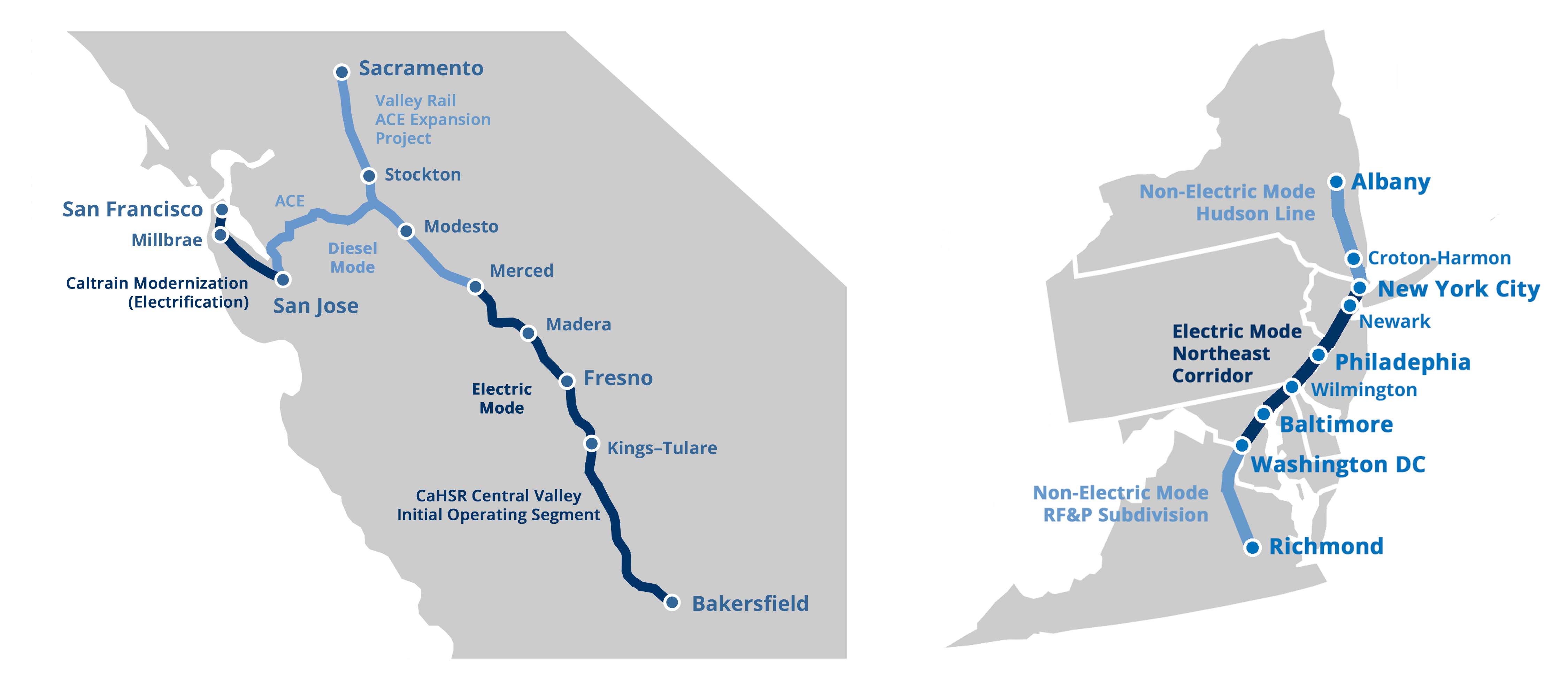

The problem is even once full electrification and track work complete on the IOS between Bakersfield and Merced, high-speed trains will be limited to these tracks, because outside the newly electrified Caltrain line between San Francisco and San Jose, the rest of the rail system is unelectrified and uses diesel trains. Much of the track is also owned by the private freight railroads BNSF and Union Pacific, which likely would oppose electrification of their right-of-way, which if approved would still take many years and billions of dollars.

This is where dual-mode trains—trainsets that can run off electricity from overhead catenary on electrified track and then onboard diesel generators over unelectrified track—come in as an intern solution for perhaps bringing high-speed rail service sooner and expanding it to Sacramento and the Bay Area over existing tracks utilized by passenger rail.

In and around New York City dual-mode locomotives have been in limited service since the 1920s due to limits on steam and diesel motive power within Manhattan, including Grand Central Terminal and Penn Station. Switching between electric and steam, later diesel locomotives at places like Croton-Harmon and New Haven was one solution, but in the 1950s the New Haven bought a fleet of EMD FL9 dual-mode diesel-electric locomotives that ran off the DC third rail in the tunnels and train sheds of Grand Central and Penn Station.

Amtrak brought FL9s to the Empire Corridor in the 1970s while the new gas-turbine Rohr Turboliners trainsets were modified to take power in from the third rail. In the 1990s the passenger railroad replaced these locomotives and trainsets with GE Genesis P32AC-DM diesel-electric locomotives which likewise run off the third rail in the New York tunnels and stations.

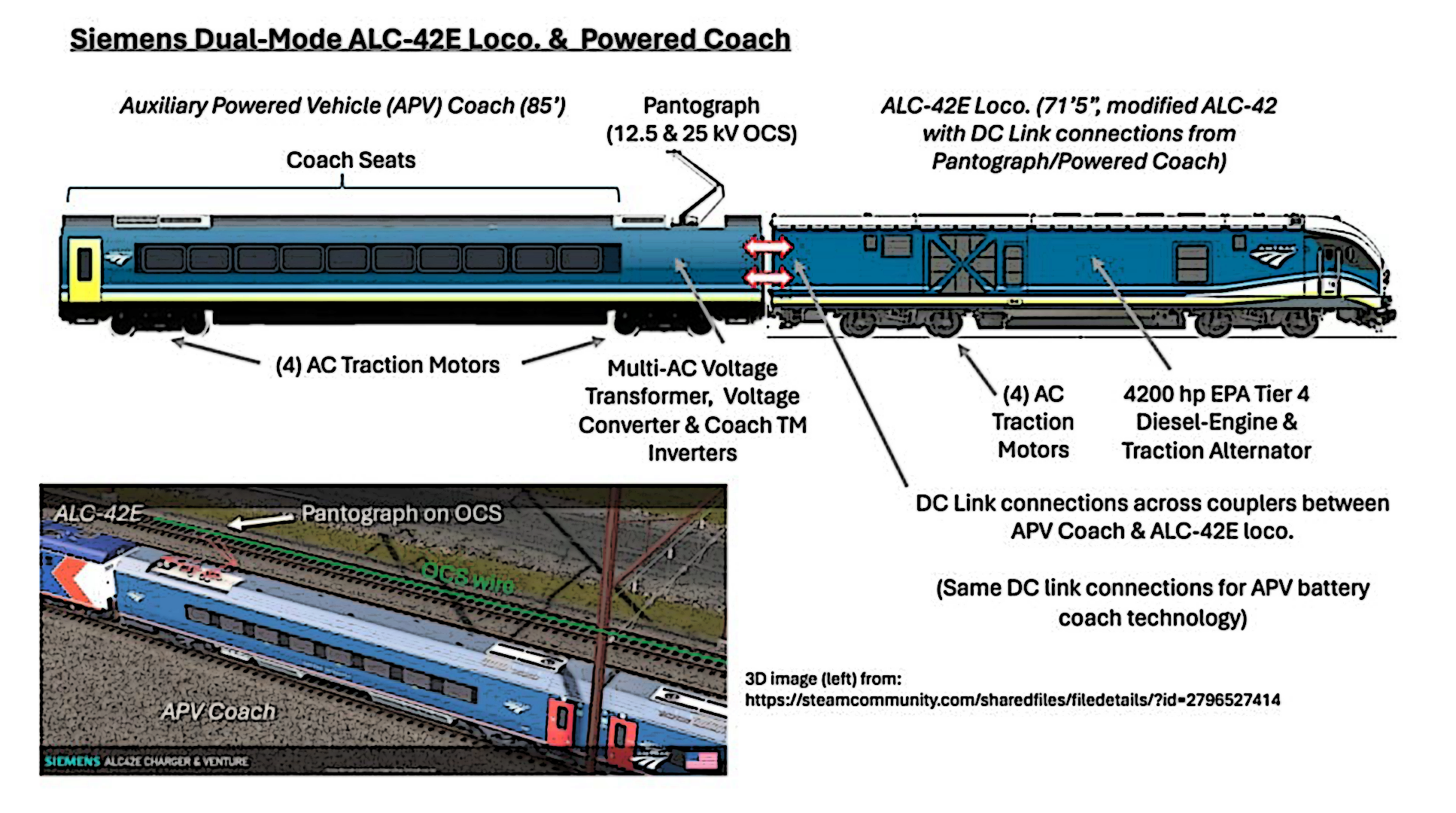

Next decade Amtrak will replace the venerable Genesis dual-modes with new ‘Airo’ trainsets from Siemens Mobility made up of Venture passenger coaches and a Charger diesel-electric that will be able to take power from a battery pack located in the adjoining coach for non-diesel operation in New York City.

The new Airo trainsets for the Northeast Corridor (NEC) however will have more extensive dual-mode capability, with the adjoining coach—labeled an Auxiliary Power Vehicle—will be equipped with a pantograph, transformer and traction motors. These trainsets will travel up to 125 MPH under electric power alone proved by the overhead catenary on the NEC.

Dual-Mode Charger-Venture trainsets offer one solution to providing a through one-seat service to Sacramento and the Bay Area over the existing rail network beyond the CaHSR’s Central Vally IOS, while utilizing the overhead catenary for zero-emission electric traction while traveling at 125 MPH over the new high-speed tracks.

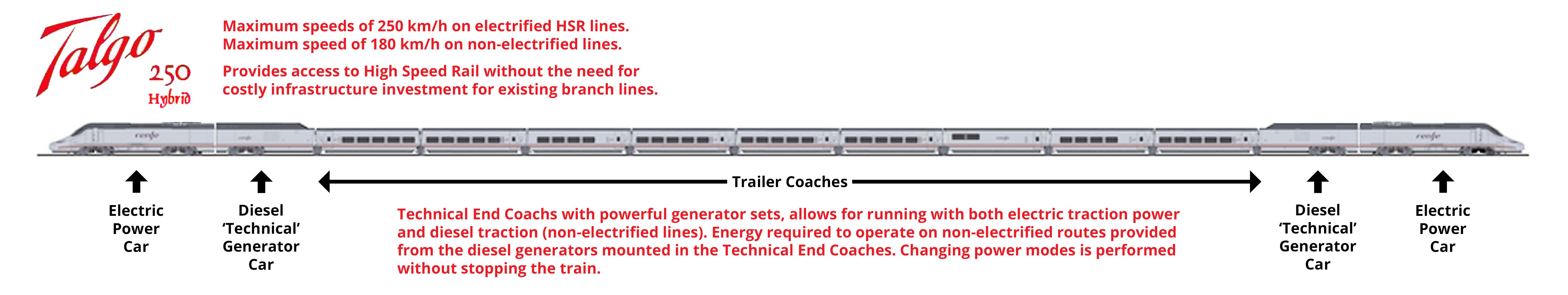

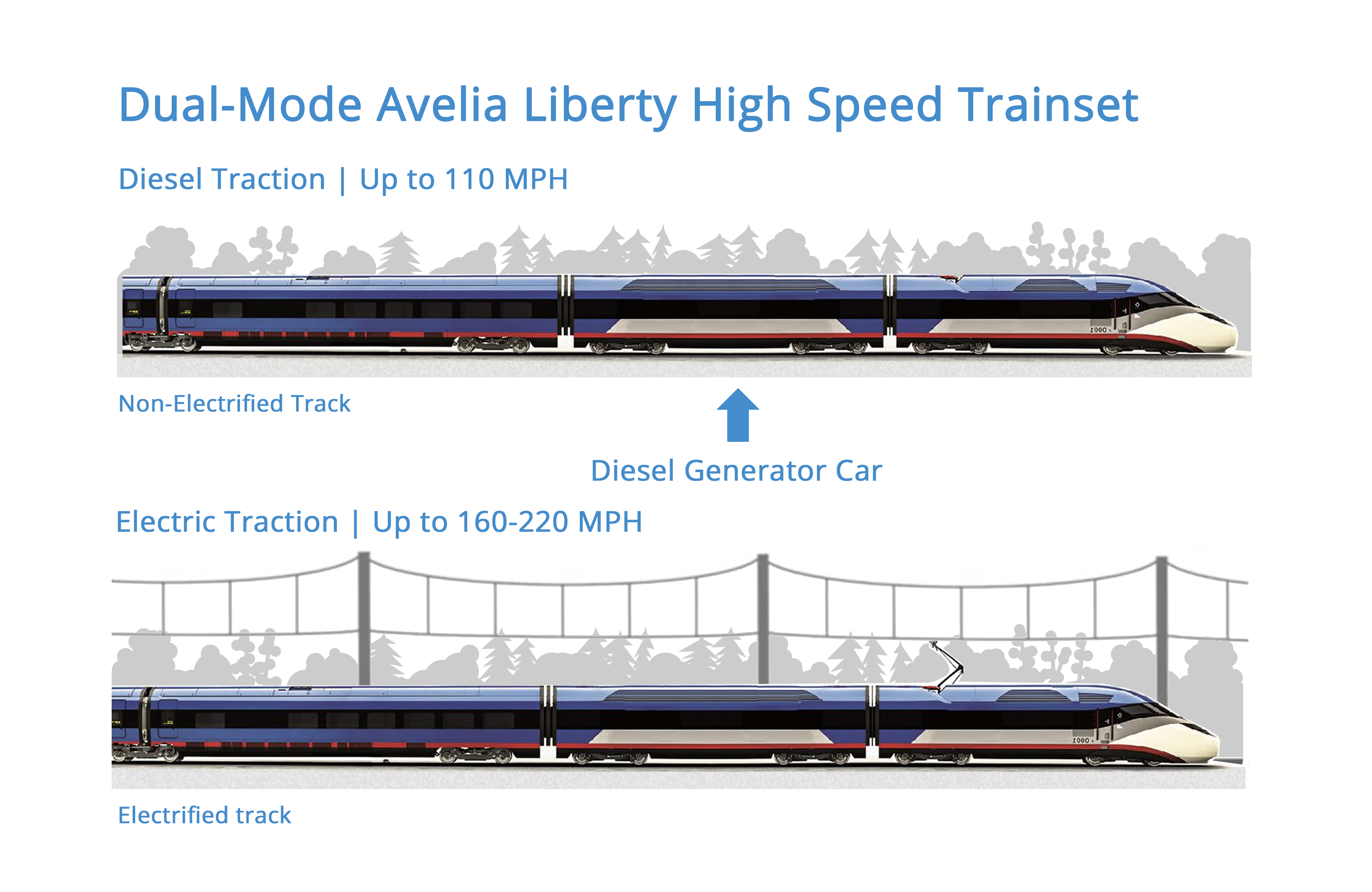

Yet there is another dual-mode solution that could allow through trains to run at the far higher speeds the new infrastructure will enable. There already is today in service a dual-mode high-speed train that runs up to 160 MPH under electric power and 110 MPH under diesel over unelectrified tracks. The Talgo 250 Dual (Renfe Class 730) in Spain wis a standard electric Talgo 250 high-speed trainset with two diesel generator cars added at each end adjacent to the electric power cars. When running beyond electrified tracks the diesel generator cars provide the power for the two adjacent electric power cars.

Dividing the diesel power between two generator cars also keeps the axle-weight down, a key point as the heavier the locomotive or rail car and the faster it moves the more stress the wheels impose upon the track (track forces)—leading to higher maintenance costs and at very high speeds even outright damage with the risk of derailment. High Speed Trains are therefore designed to be light weight with superior suspension and wheel design (wheel profile) so to keep track forces at an economically sustainable level for maintenance of the track structure (heavily built for high-speed rail) of steel rails, concrete ties, and ballast.

Diesel trains with their heavy prime mover only travel in commercial service up to 125 MPH due to their weight, to travel faster the necessary power required to propel a train up to 150 MPH and higher would result in a locomotive too heavy for the track. This is why all high-speed trains today traveling over 125 MPH are electric, with light yet high-power gas-turbines having been utilized in several prototypes. For the Talgo 250 Dual the diesel engines only have to move the train at 110 MPH on unelectrified track and the weight of the generator cars are light enough for moving at 160 MPH when the train is in electric mode on high-speed tracks.

While Spain has built out one of the world’s largest high-speed rail networks, there are still cities beyond these new lines, the Talgo 250 Dual allows these cities to be served directly by high-speed trains. There is no reason why the same could not be done with the two high-speed train designs approved for use in North America—the Alstom Avelia Liberty and the Siemens American Pioneer—and the advantages of doing so are readily apparent for California and the rest of North America.

There are several major differences between the rail system of North America and the rest of the world that make building high-speed rail far more difficult. Unlike most other nations, our rail network is primarily privately owned, moves large amounts of freight, and is almost entirely unelectrified outside Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor and some publicly owned commuter railways. And worse, the private freight railroads are mostly opposed to electrification of their tracks on their right-of-way.

For example, the Class One freight railroad CSX in its agreement for the Commonwealth of Virginia to purchase half the right-of-way of its RF&P Subdivision between Washington DC and Richmond for new dedicated passenger tracks, had the state government agree to a 90 MPH top speed and no electrification. It’s for this reason that Amtrak will be introducing dual-mode Airo trainsets for its Northeast Regional services. Currently the locomotives for the Regional trains to and from Virginia are changed at Washington Union Station, a process that takes 20 minutes, which the dual-mode Airos will eliminate.

Dual-Mode high-speed trains with speeds of 160-to-220 MPH would allow new electrified high-speed tracks to be built, perhaps along Interstate rights-of-way like Brightline West, with existing freight right-of-way utilized to enter dense urban centers. This could dramatically lower the costs of building out high-speed rail across the United States and Canada, by leveraging existing privately owned railroad rights-of-way into dense urban centers. It would allow for incremental construction of new high-speed track, California being the foremost example with its current phased multi-decade construction.

And this would directly socioeconomically benefit Upstate New York, the Southern Tier being the manufacturing location for North America’s two current high-speed trains: the Avelia Liberty by Alstom in Hornell and American Pioneer by Siemens in Horseheads. If high-speed rail can be built at a lower cost in North America, that would provide additional orders to Alstom and Siemens, providing for continual industrial employment for New Yorkers. New York State could even order a few dual-modes sets for through high-speed service from Albany to Washington DC and Richmond, more firmly tying the Capital District into the Northeast Corridor.

New York State should follow the example of California which has help fund the development of hydrogen fuel cell locomotive prototypes, by partnering with either Alstom or Siemens or both rail manufacturers, to fund, build, and test dual-mode variants of the Avelia Liberty and American Pioneer high-speed trainsets. This investment should pay dividends in continual employment for New Yorkers working in the Upstate NY rail manufacturing industry.

ABOVE: In California, Dual-Mode High Speed Trains would allow direct through service from the Bay Area and Sacramento to Fresno and Bakersfield, with trains running up to 220 MPH on the new high-speed tracks of the Central Valley Initial Operating Segment and at 80 to 90 MPH over existing tracks, now being upgraded for expanded Altamont Corridor Express commuter service as the Valley Rail Project. On the East Coast, Dual-Mode High Speed Trains could allow Acela service (or another branded service) to be expanded to new cities, including Albany and Richmond, that are connected to the Northeast Corridor by unelectrified diesel operated rail lines.

ABOVE: Alstom won the contract for the next generation Acela Express trainsets in 2016, with manufacturing of the 28 trains occurring at their plant in Hornell, NY. Alstom will also provide long-term technical support and supply spare components and parts for the trainsets.

Dual-Mode Avelia Liberty

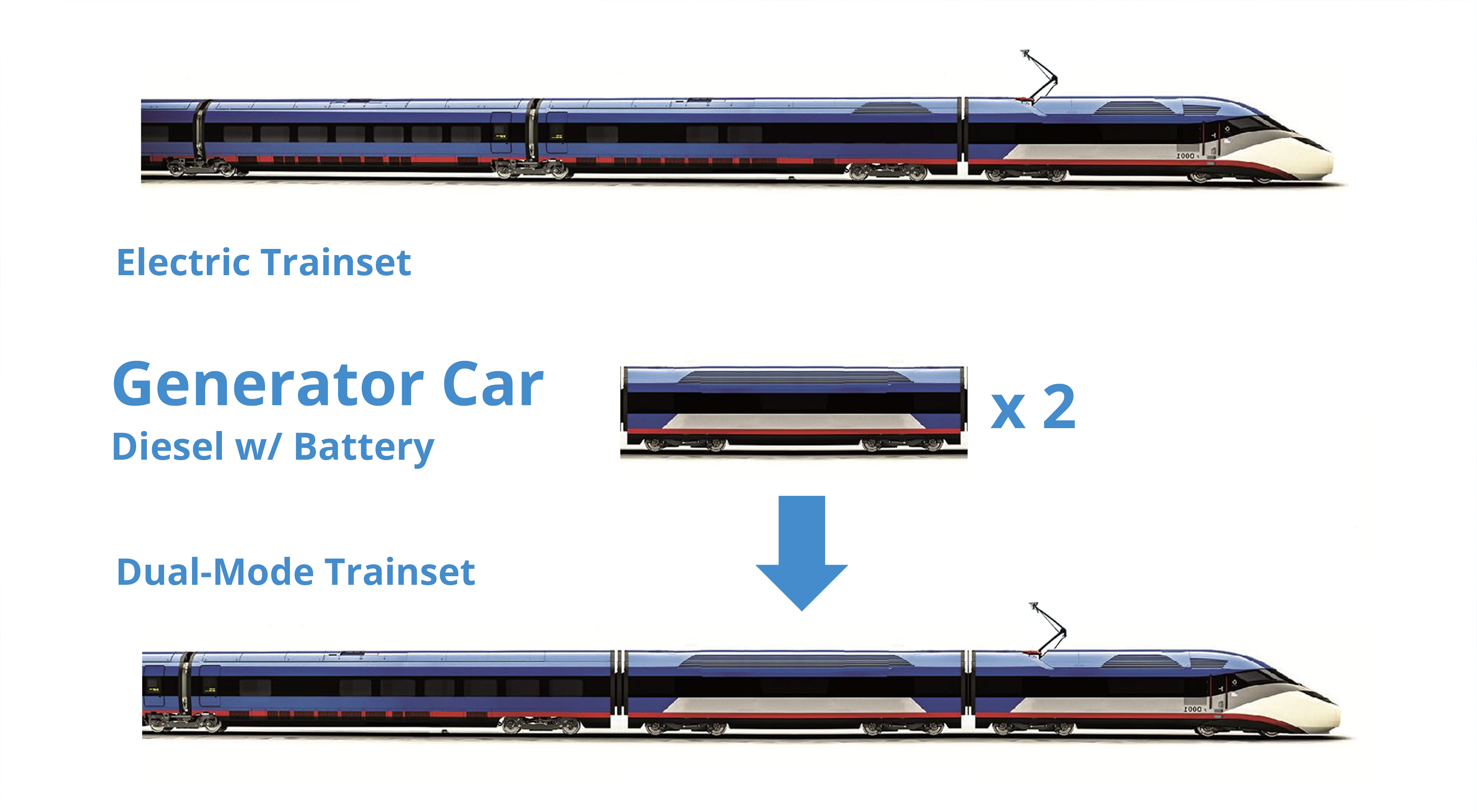

Alstom is likely best place to create a dual-mode high-speed train by replicating the Talgo 250 Dual because first, like the Spanish train, the Avelia Liberty has its motive power concentrated in two power cars located at each end of the trainset. To create a dual-mode train, all Alstom needs to do is same as Talgo and insert two generator cars, each adjacent to the end power cars.

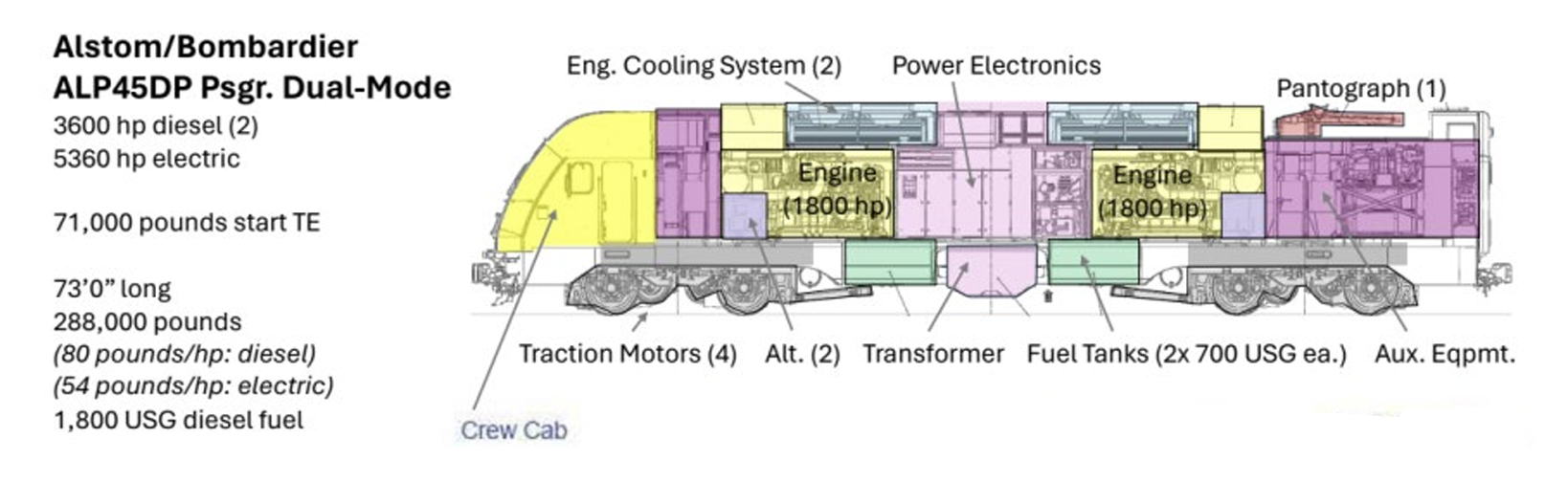

The second reason is that in an existing locomotive design—the Bombardier ALP-45DP—Alstom already has the components to create a generator car. The ALP-45DP was designed to run under electric power at 125 MPH on the Northeast Corridor and at 100 MPH on the unelectrified branch lines of New Jersey Transit—and thus to fit the required equipment for both electric and diesel traction it is a heavy and mechanically complex locomotive.

What makes the ALP-45DP useful for “kitbashing” a generator car for the Avelia Liberty is that instead of a single diesel prime mover—the Siemens Charger has a single Cummins QSK95 16-cylinder diesel engine providing 4200 HP with the weight of 28,475 LB—the locomotive has two Caterpillar 3512C HD 12-cylinder diesel engines, each weighing 14,145 LBs while producing 1800 HP; though the engine according to Caterpillar has a maximum power rating of 2400 HP.

To create the two generator cars, the frame and body shell from the existing Avelia power car could be adapted to contain one half of the diesel powertrain from the ALP-45DP, each car hosting one Caterpillar 3512C HD engine and associated supporting components—including the alternator, cooling equipment, electronics, and fuel tanks. A bank of plug-in batteries likely could be included to allow hybrid operation, increasing fuel efficiency while reducing emissions. All together combined the weight of the generator car should not exceed that of the electric power car, while suppling the electrical power necessary to run on unelectrified tracks up to 90-to-110 MPH.

A question is would inclusion of the two generator cars limit top speeds to the 160 MPH of the Talgo 250 Dual? Likely no, as the top speed of the all-electric Talgo 250 is also 160 MPH (250 KM/H). I would think so as long as the weight of the diesel generator cars is the same as the electric power cars, that a dual-mode Avelia Liberty should have no issues at the design 186 MPH speed of the all-electric tilting version, and perhaps for the maximum potential design speed of 220 MPH.

ABOVE: Siemens Mobility in 2024 won the contract to build the high speed trainsets for the Las Vegas-California ‘Brightline West’ project, with the ‘American Pioneer 220’ trains to be manufactured in Horseheads, NY. IMAGE CREDIT: Siemens Mobility via Press Kit

Dual-Mode American Pioneer 220

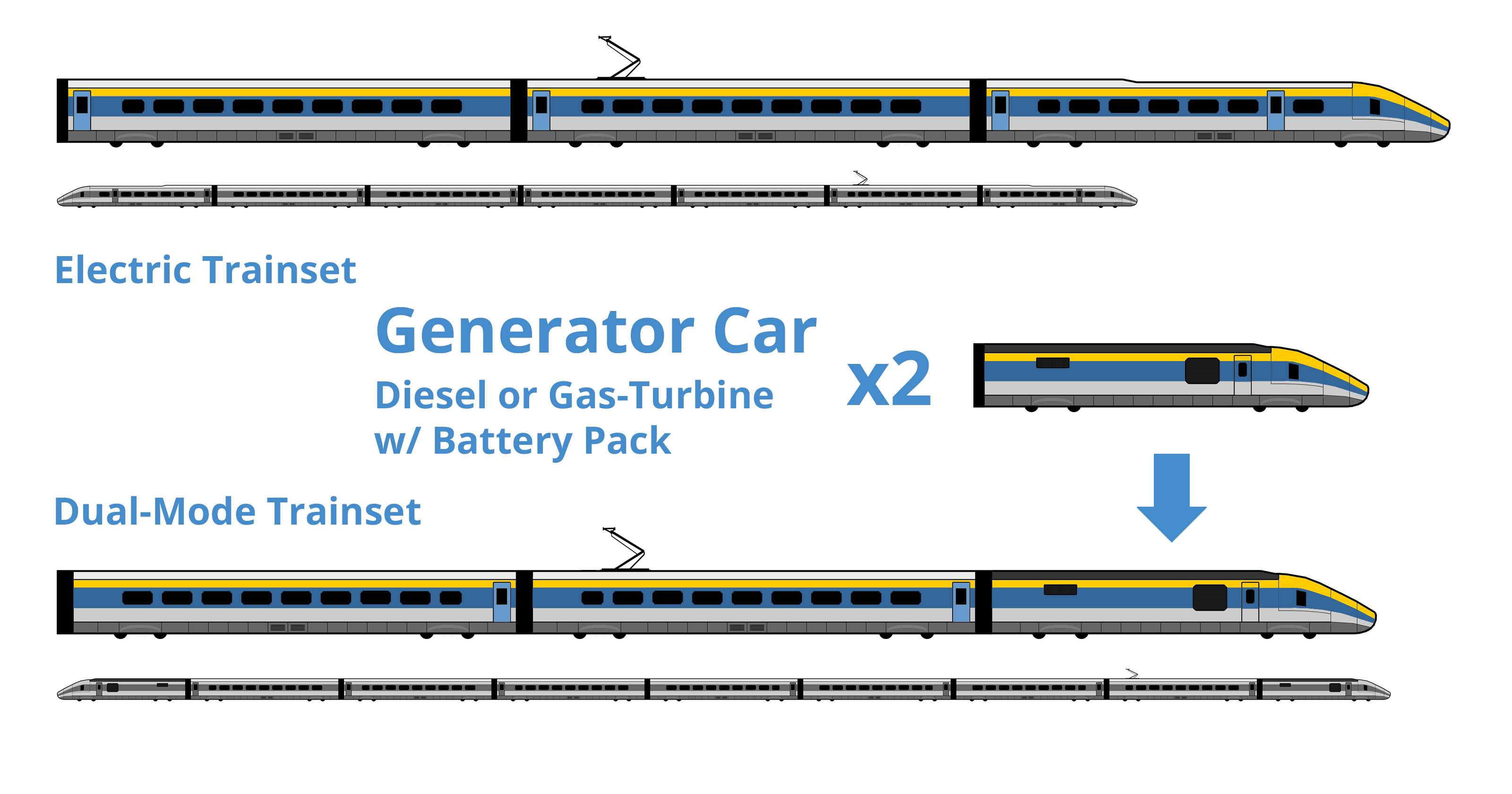

Siemens may be in a slightly less advantageous position in developing a dual-mode version of the American Pioneer than Alstom, the key difference being that the Pioneer is a Electric Multiple Unit (EMU) train where the motive power instead of being concentrated in one or two power cars, is distributed across the trainset, with the traction motors and other equipment under the floor of each passenger car, with power from the overhead catenary provided by a pantograph over one of the cars.

However, like the Talgo 250 Daul and conceptional dual-mode Avelia Liberty, the addition of two generator cars to the Pioneer trainset would allow it to operate extensively on unelectrified track. The logical location for the two required generator cars would be on each end of the trainset in a structurally beefed-up modified Pioneer coach design that in addition to the diesel prime mover (and likely battery pack) would include the driver’s control cab and streamline front end. Given that the Charger passenger locomotive utilizes the 4200 HP Cummins QSK95 16-cylinder diesel with a weight of 28,475 LB, Siemens perhaps might opt for two 2200 HP Cummins QSK50 16-cylinder diesel engines weighing 13,823 LB for the generator cars.

When operating on unelectrified track the two generator cars would feed electricity to the traction motors of the rest of the train the same way the pantograph feeds electricity from the overhead catenary when on electrified track. The generator cab cars would weight a lot more than the cars of the rest of the trainset, but they shouldn’t weigh more than the power cars of the Avelia Liberty, and thus the trainset should be well capable of 186 MPH (300 KM/H) standard for high-speed railways around the world, and likely perhaps the 220 MPH design speed of for the all-electric American Pioneer 220.

BELOW: The announcement in September 9, 2024 of Siemens Mobility establishing a high-speed rail production facility in Horseheads. Photo includes: Chairman of Chemung County Legislature, Mark Margeson, Deputy County Executive of Chemung County, Jennifer Furman, Special Assistant to the International President for the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (IAM) Rail Division, Josh Hartford, FRA Administrator, Amit Bose, President and CEO of Siemens USA, Barbara Humpton, U.S. Senator, Chuck Schumer, CEO of Brightline, P. Michael Reininger, and President and CEO of Siemens Mobility North America, Marc Buncher. PHOTO CREDIT: Siemens Mobility via Press Kit

Conceptional Dual-Mode High Speed Rail Corridors

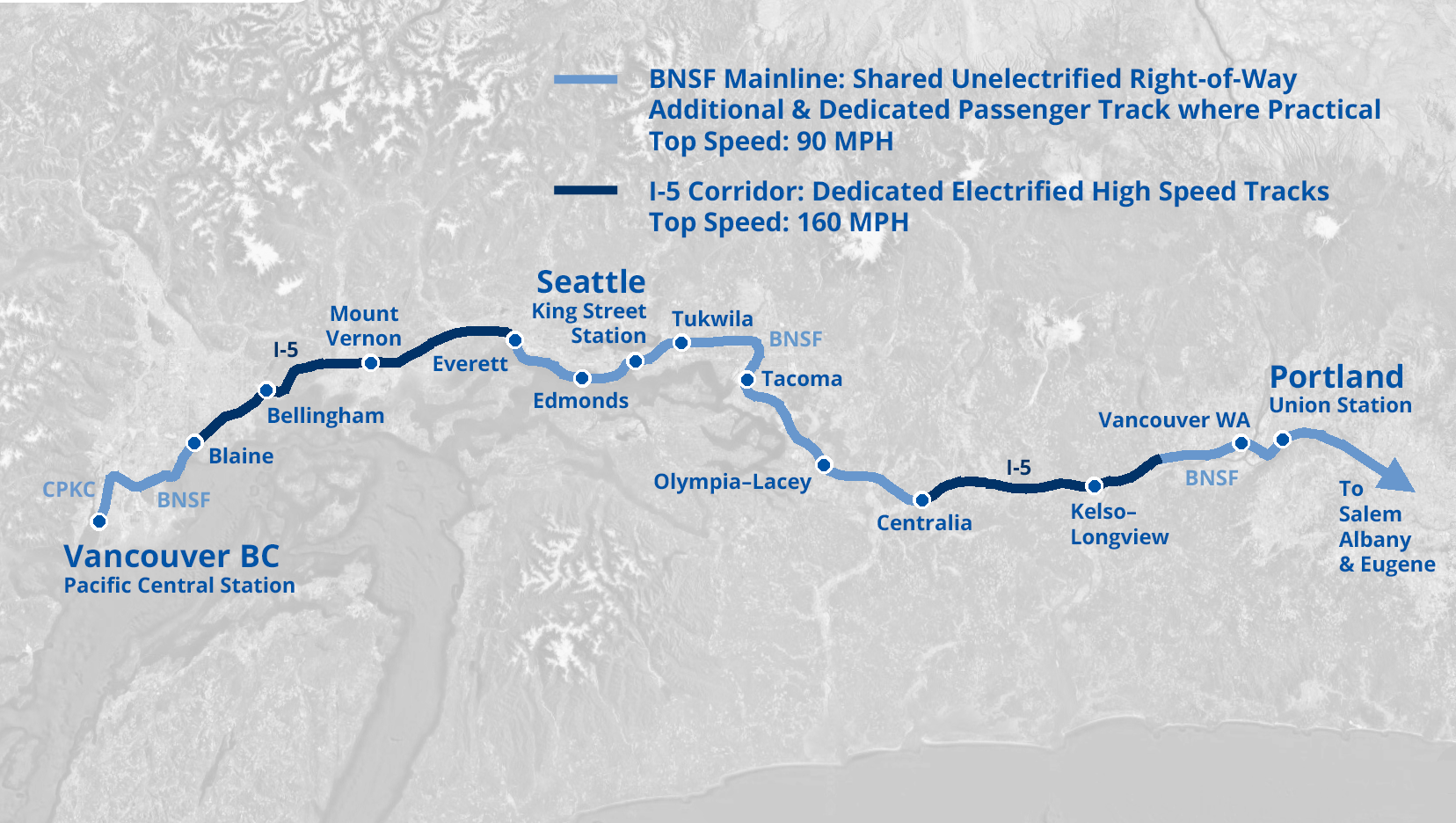

Cascadia

A high-speed rail service connecting Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver BC by extensively utilizing existing BNSF mainline right-of-way (Seattle, Scenic, and Bellingham subdivisions) with new dedicated/additional mainline track at speeds up to 90 MPH, with two long segments of dedicated high-speed track (likely 160 MPH due to highway curvature) utilizing the right-of-way of the I-5 interstate in rural areas.

Arizonia

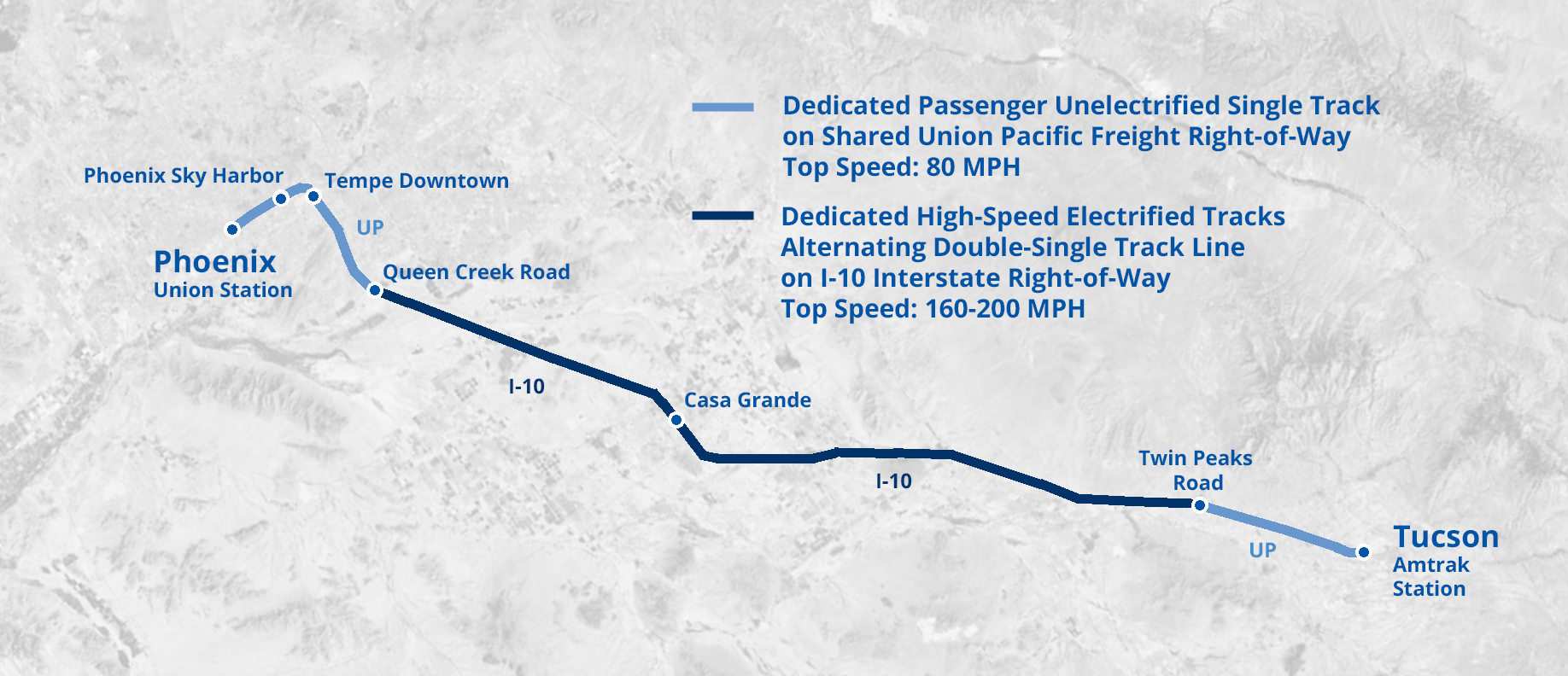

A high-speed rail service running primarily along the I-10 interstate right-of-way with dedicated high-speed track, but utilizing with lower speed dedicated passenger track the Union Pacific freight right-of-way of its Gila Subdivision (Sunset Transcontinental Mainline) into Tuscan to the Amtrak station, and in Phoenix metro the secondary Tempe Industrial Lead and Phoenix Subdivision to the old Southern Pacific Union Station.

Alberta

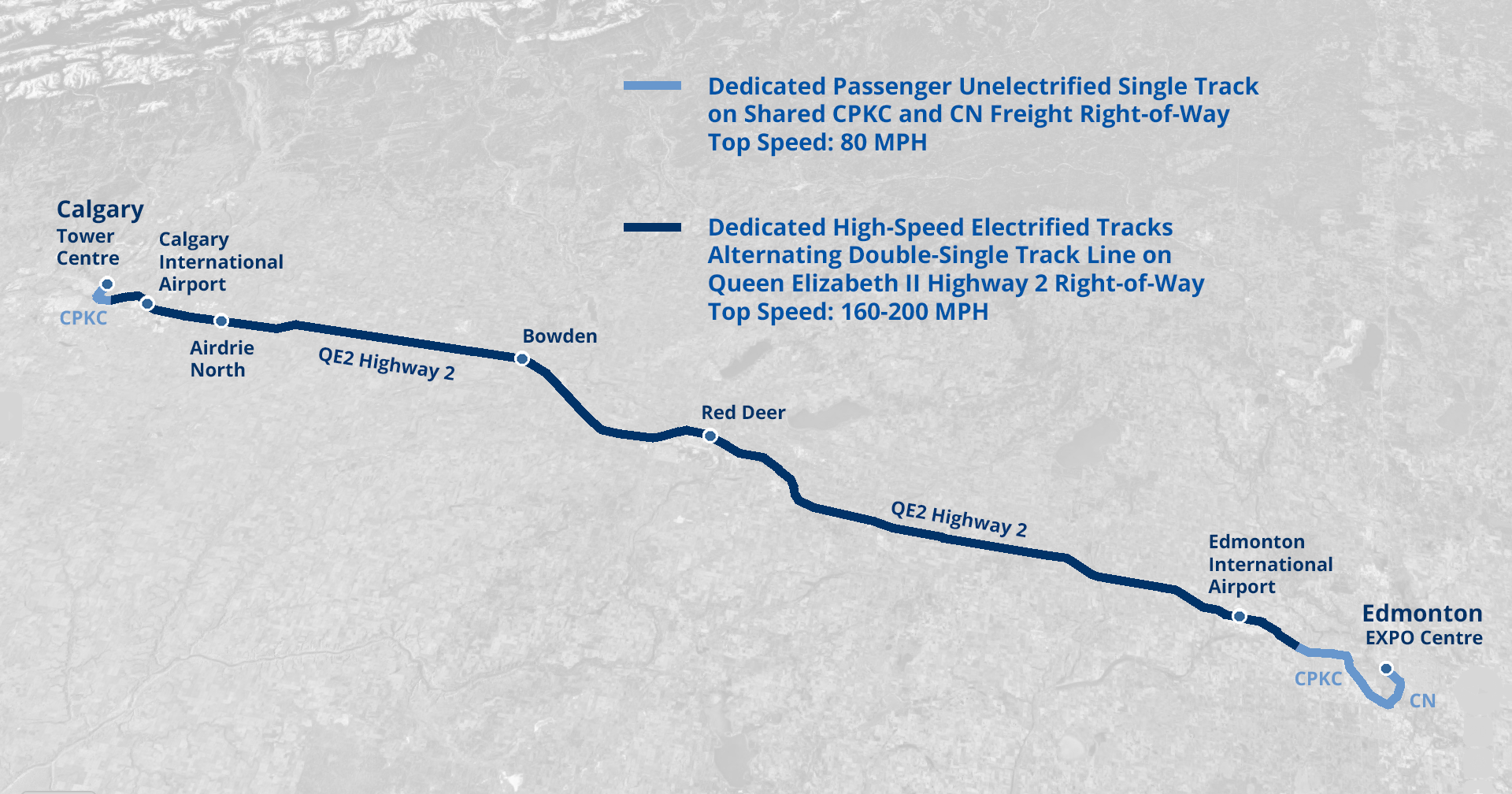

A high-speed rail service running primarily along the Queen Elizabeth II Highway 2 expressway with dedicated high-speed track at speeds of 160-to-220 MPH, utilizing with dedicated passenger track the freight right-of-way of CPKC and CN to enter the urban centers of Calgary and Edmonton.